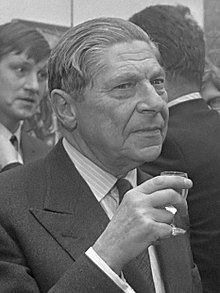

While Arthur Koestler was awaiting execution after being captured and sentenced to death by Francoist forces as a communist spy during the Spanish Civil War, he had a mystical experience. Formerly a Marxist materialist who believed the universe was governed by “physical laws and social determinants”, he glimpsed another reality. The world now seemed instead as “a text written in invisible ink”.

The experience left him untroubled by the prospect of his imminent death by firing squad. At the last moment, he was traded for a prisoner held by Republican forces. But the epiphany of another order of things that came to him in the prison cell stayed with him for the rest of his days, informing his great novel of communist faith and disillusion, Darkness at Noon (1940), his later writings on the history of science, and a lifelong interest in parapsychology.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Koestler was a pivotal figure in the post-war generation that rejected communism as “the God that failed”— the title of a celebrated book of essays, edited by the Labour politician Richard Crossman and published in 1949, to which Koestler contributed. The ex-communists of this period followed a variety of political trajectories. André Gide, another contributor to the collection, abandoned communism, after a visit to the Soviet Union in 1936, to become a writer on issues of sexuality and personal authenticity.

Koestler was a pivotal figure in the post-war generation that rejected communism as “the God that failed”— the title of a celebrated book of essays, edited by the Labour politician Richard Crossman and published in 1949, to which Koestler contributed. The ex-communists of this period followed a variety of political trajectories. André Gide, another contributor to the collection, abandoned communism, after a visit to the Soviet Union in 1936, to become a writer on issues of sexuality and personal authenticity.

The rise of post-truth liberalism

Other ex-communists became social democrats, while a few became militant conservatives or lost interest in politics completely. Stephen Spender, poet and novelist and author of Forward from liberalism (1937), morphed into a cold-war liberal. James Burnham, a friend and disciple of Leon Trotsky, rejected Marxism in 1940 to reappear as a militant conservative, publishing The Suicide of the West: the meaning and destiny of liberalism (1964) and eventually being received into the Catholic Church. All of them became communists in a time when liberalism had failed. All were able to return to functioning liberal societies when they abandoned their communist faith.

When interwar Europe was overrun by fascism, the Soviet experiment seemed to these writers to be the best hope for the future. When the experiment failed, and they renounced communism, they were able to resume their life and work in a recognisably liberal civilisation.

Post-war global geopolitics may have been polarised, with a precarious nuclear stand-off between the Soviet Union and the US and its allies. Liberal societies may have been flawed, with McCarthyism and racial segregation stains on the values western societies claimed to promote. But liberal civilisation was not in crisis. Large communist movements may have existed in France, Italy and other European countries, while Maoism attracted sympathetic interest from alienated intellectuals. But even so, liberal values were sufficiently deep-rooted that in most western countries they could be taken for granted. The West was still home to a liberal way of life.

The situation is rather different today. Liberal freedoms have been eroded from within, and dissidents from a new liberal orthodoxy face exclusion from public institutions. This is not enforced by a totalitarian state, but by professional bodies, colleagues and ever vigilant internet guardians of virtue. In some ways, this soft totalitarianism is more invasive than that in the final years of the Soviet bloc.

How Thatcherism produced Corbynism

The values imposed under communism were internalised by few among those who were compelled to conform to them. Ordinary citizens and many communist functionaries were a bit like Marranos, the Iberian Jews forced to convert to Christianity in mediaeval and early modern times, who secretly practised their true religion for generations or centuries afterwards. Such fortitude requires rich inner resources and an idea of truth as something independent of subjective emotion and social convention. There are not many Marranos in the post-liberal west.

Some have attempted to revive classical liberalism, an anachronistic project that harks back to a time when western values could command a global hegemony. Others have opted for a hyperbolic version of liberalism in which western civilisation is denounced as being a vehicle for global repression.

In this alt-liberal ideology, the central values of classical liberalism — personal autonomy and the rejection of tradition in favour of critical reason — are radicalised and turned against the liberal way of life. A heretical cult, alt-liberalism is what liberalism becomes when it tears up its roots in Jewish and Christian religion. Today it is the ruling ideology in much of the academy and media.

In these conditions one might suspect self-censorship, since anyone expressing seriously heterodox views risks a rupture in their professional life. Yet it would be a mistake to think alt-liberals are mostly cynical conformists. Since practising cynics realise that the views they are publicly promoting are actually false, cynicism presupposes the capacity to recognise truth. In contrast, alt-liberals appear wholly sincere when they denounce the society that privileges and rewards them. Unlike the Marranos, whose public professions concealed another view of the world, alt-liberals conceal nothing. There is nothing in them to conceal. They are expressing the prevailing western orthodoxy, which identifies western civilization as being uniquely malignant.

Deluded liberals can't keep clinging to a dead idea

Of course, civilisational self-hatred is a singularly western conceit. Non-western countries — China, India and Russia, for example— are increasingly asserting themselves as civilisation-states. It is only western countries that denounce the civilisation they once represented. But not everything is as it seems. Even as they condemn it, alt-liberals are affirming the superiority of the West over other civilisations. Not only is the West uniquely destructive. It is only the West — or its most advanced section, the alt-liberal elite — that has the critical capacity to transcend itself. But to become what, exactly? Lying behind these intellectual contortions is an insoluble problem.

In his essay in The God that failed Gide wrote: “My faith in communism is like my faith in religion. It is a promise of salvation for mankind.” Here Gide acknowledged that communism was an atheist version of monotheism. But so is liberalism, and when Gide and others gave up faith in communism to become liberals, they were not renouncing the concepts and values that both ideologies had inherited from western religion. They continued to believe that history was a directional process in which humankind was advancing towards universal freedom.

Without this idea, liberal ideology cannot be coherently formulated. That liberal societies have existed, in some parts of the world over the past few centuries, is a fact established by empirical inquiry. That these societies embody the meaning of history is a confession of faith. However much its devotees may deny it, secular liberalism is an oxymoron.

A later generation of ex-communists confirms this conclusion. Trotskyists such as Irving Kristol and Christopher Hitchens who became neo-conservatives or hawkish liberals in the Eighties or Nineties did not relinquish their view of history as the march towards a universal system of government. They simply altered their view as to the nature of the destination.

You're reaping what you sowed, liberals

Instead of world communism, it was now global democracy. Western interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq and later Libya were wars of liberation backed by the momentum of history. The fiascos that ensued did not shake this belief. The liberalism of these ex-Trotskyists was yet another iteration of monotheistic faith.

Alt-liberals aim to deconstruct monotheism, along with the grand narratives it has inspired in secular thinkers. But what emerges from this process? Once every cultural tradition is demolished, nothing remains. In principle, alt-liberalism is an empty ideology. In practice it defines itself by negation.

Populist currents are advancing throughout the West and supply the necessary antagonist. The old liberalism that prized tolerance no longer survives as a living force. Iconoclasts who smash statues of colonial-era figures are raging at an enemy that has long since surrendered. An impish avatar of a vanished liberal hegemony, alt-liberalism needs populism if it is to survive.

Resistance to populist movements fills what would otherwise be an indeterminacy at the heart of the alt-liberal project. Privileged woke censors of reactionary thinking and incendiary street warriors are mutually reinforcing forces. At times, indeed, they are mirror-images of one another. Both have targeted the state of Israel as the quintessential embodiment of western evil, for example. Not only do alt-liberals and populists need one another. They share the same demonology.

Today's voguish communists should remember Budapest

Viewing the post-liberal West from a historical standpoint, one might conclude that it will suffer the same fate as communism. Facing advancing authoritarian powers and weakened from within, a liberal way of life must surely vanish from history. True, some traces will remain. Even in societies where denunciation for reactionary thinking is a pervasive practice, fossil-like fragments of ancient freedoms will be found scattered here and there. But surely the global liberal order will finally implode, leaving behind only defaced remnants of a civilisation that once existed.

In fact, any simple analogy between the fall of communism and the decay of liberalism is misleading. The difference is that old-style liberals have nowhere to go. To be sure, they could abandon any universalistic claim for their values and think of them as inhering in a particular form of life — one that is flawed, like every other, but still worthwhile.

Yet this is hardly a viable stance at the present time. For one thing, this way of life is under siege in what were once liberal societies. Yet liberals cannot help but see themselves as carriers of universal values. Otherwise, what would they be? Anxious relics of a foundering civilisation, seeking shelter from a world they no longer understand.

There may be no way forward for liberalism. But neither is the liberal West committing suicide. That requires the ability to form a clear intention, which the West shows no evidence of possessing. Nothing as dramatic or definitive will occur. Koestler and the ex-communists of his generation regarded communism as the God that failed because they once believed it to be the future. Today almost no one any longer expects liberal values to triumph throughout the world, but few are able to admit it — least of all to themselves. So instead they drift.

It is not hard to detect a hint of nostalgia among liberals for the rationalist dictatorships of the past. Soviet communism may have been totalitarian, but at least it was inspired by an Enlightenment ideology. Though it has killed far fewer people, Putin’s Russia is far more threatening to the progressive world-view.

China, on the other hand, is envied as much as it is feared. Its rulers have renounced communism, but in favour of a market economy, globalisation and a high-tech version of Bentham’s Panopticon — all of them imported western models. The liberal west may be on the way out, but illiberal western ideas still have a part in shaping the global scene.

When ex-communists became liberals, they shifted from one secular faith to another. Troubled liberals today have no such option. Fearful of the alternatives, they hang on desperately to a faith in which they no longer believe. Liberalism may be the other God that failed, but for liberals themselves their vision of the future is a deus absconditus, mocking and tormenting them as the old freedoms disappear from the world.